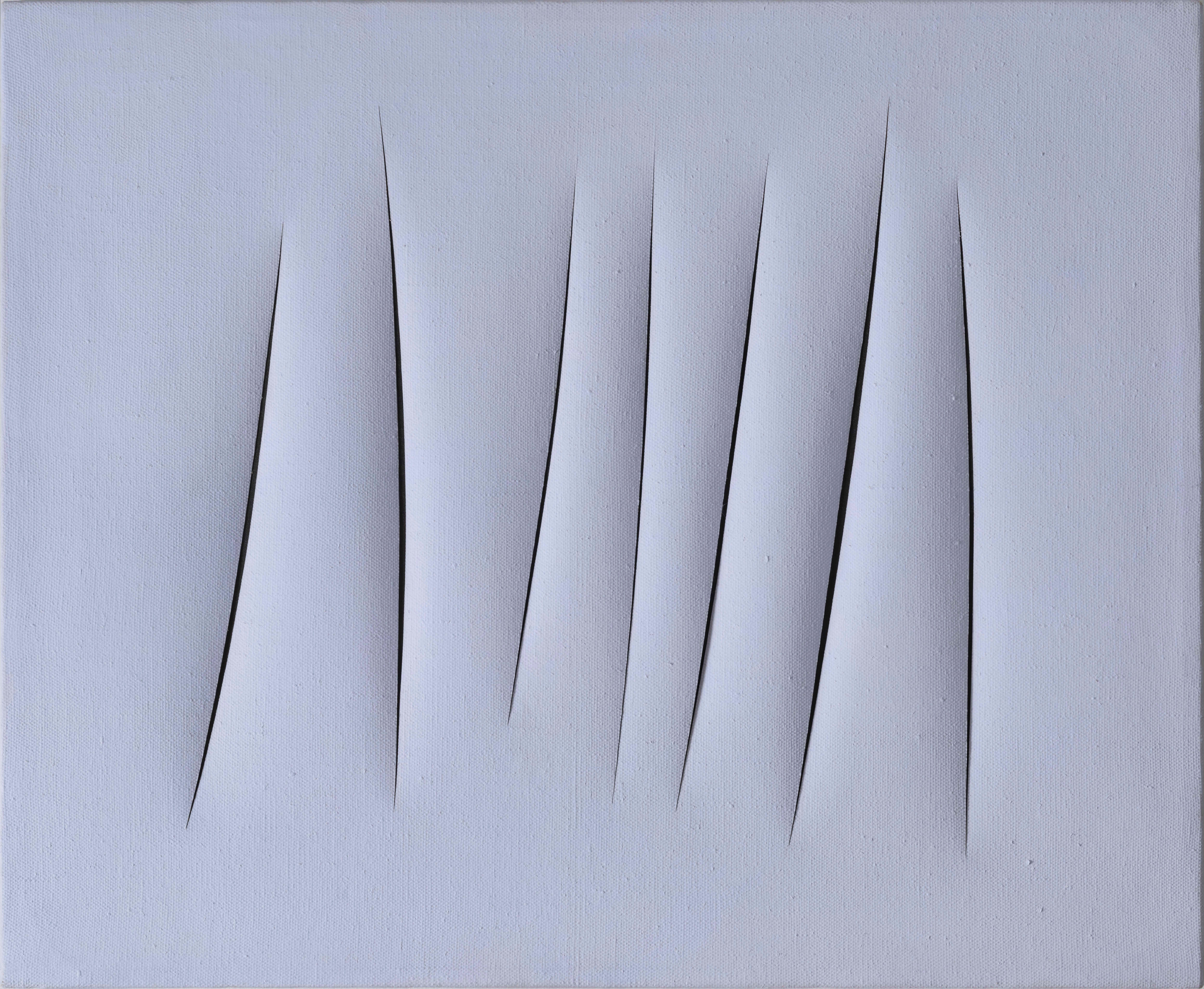

Lucio Fontana

b. 1899, Rosario de Santa Fé, Argentina

d. 1968, Comabbio, Italy

Concetto Spaziale, Attese (Spatial Concept, Waiting)

1964

Water-based paint on canvas

60 x 73 cm (23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in.)

Provenance

with Galleria Notizie, Turin;

with Galleria Sperone, Turin;

Private collection, Veduggio;

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

with Galleria Sperone, Turin;

Private collection, Veduggio;

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Literature

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnements spatiaux, Brussels, 1974, vol. II, no. 64 T 47, illustrated p. 155.

E. Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan, 1986, vol. II, no. 64 T 47, illustrated p. 523.

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Milan, 2006, vol. II, no. 64 T 47, illustrated p. 714.

E. Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan, 1986, vol. II, no. 64 T 47, illustrated p. 523.

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Milan, 2006, vol. II, no. 64 T 47, illustrated p. 714.

Description

Seven slashes rhythmically rupture the pristine surface of Lucio Fontana’s Concetto Spaziale, Attese, revealing delicate slivers of the darkness beyond the picture plane. A supremely elegant iteration of Fontana’s best-known series, the tagli, this work was executed in 1964, a moment when the artist was at the height of his powers. While simultaneously creating his iconic Fine di Dio works—large, otherworldly oval canvases rent open with myriad punctures—Fontana continued to explore the powerful aesthetic and symbolic potential of his sleek, sophisticated slashes in the works which have come to define the movement he presciently founded, namely Spatialism. With the slash, an act at once destructive and revelatory, iconoclastic and iconic, Fontana tore through the previously sacrosanct pictorial surface, integrating a new spatial dimension into the picture plane and in so doing, significantly redefined the boundaries of painting.

Concetto Spaziale, Attese offers an inexorable commentary on the post-war society in which it was created. Unlike his contemporary Alberto Burri, Fontana chose to turn away from the destruction, both physical and psychological, that the Second World War had wrought upon mankind, and instead focus single-mindedly upon the future, embracing all the possibilities and excitement of this great unknown. Living and working in Italy in the years immediately following the war—Fontana had returned to Milan to find his pre-war studio bombed to the ground, while Burri returned having served as a medic in the Italian army before enduring incarceration in Texas—both artists were similarly impelled to find a new artistic language to embody the post-war period in which they found themselves. While they both believed that traditional modes of painting and sculpture had no place in the post-war era, they found radically different modes of expression with which to better express the paradoxical sentiments that beset these strange and unprecedented times.

As Fontana declared, “Man today is too bewildered by the vastness of his world, he is too overwhelmed by the triumph of Science, he is too dismayed by the new inventions which follow one after the other, to be able to find himself in figurative painting. What is needed is an absolutely new language, a ‘Gesture’ purifed of all ties with the past, which gives expression to this state of despair, of existential anguish’ (Fontana, quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, Venice, and Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2006–7, p. 23).

Fascinated by science and technology, Fontana looked resolutely skywards, watching with ever increasing awe as the earth’s atmosphere was breached, first with satellites, and then as man himself conquered space. Fontana was determined, as the Futurists had been before him, to ensure that his art reflect these pioneering new advances, quickly recognising that painting and sculpture were too inherently limited to convey the extraordinary concepts of space and time so recently discovered. In the face of explosive technological and scientific innovation and change, what use, he asked, did illusionistic painted representations on canvas have? “Think about when there are big space stations”, he asked. “Do you think that the men of the future will build columns with capitals there? Or that they will call painters to paint?... No, art, as it is thought of today, will end” (Fontana, quoted in A. White, “Art Beyond the Globe: Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Identity,” emaj, 3, 2008, p. 2).

Contemporary art, Fontana believed, needed to come out of its frame and off its pedestal to incorporate and therefore exist in real time, space and movement. It was upon his return to Milan in 1947 following a seven-year sojourn in Buenos Aires that these ideas took shape. While in Argentina, he had already published a manifesto, the Manifesto Blanco, in which, borrowing the rhetoric of his Futurist forebears, Fontana denounced traditional forms of painting and sculpture, instead calling for an art that embodied the spirit of the intrepid, rapidly changing times. “We need a change in essence and in form”, the manifesto declared. “We need to go beyond painting, sculpture, poetry, and music. We need a greater art in harmony with the requirements of the new spirit” (Manifesto Blanco, 1946, quoted in E. Crispolti and R. Siligato, eds., Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, 1998, p. 115). A year later, Fontana presented a second tract entitled Primo Manifesto Spaziale, which presented the central tenets of Fontana’s newly-founded Spatialism, the movement to which he would remain devoted for the rest of his career. “We refuse to believe that science and art are two distinct facts, that the gestures accomplished by one of the two activities cannot also belong to the other”, Fontana declared in this text, surmising the central aspects of the movement. “Artists anticipate scientific gestures, scientific gestures always provoke artistic gestures” (Primo Manifesto Spaziale, 1947, quoted in ibid., p. 118).

Along with the space race, Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity had hit Fontana with the force of a revelation. Discovering the scientist’s revolutionary concepts, Fontana sought in his art to look beyond the bounds of reality and representation: just as Einstein expounded the existence of the fourth dimension, so Fontana sought to capture this concept in artistic form. “Spatial is what is beyond the perspective...the discovery of the cosmos...Which are all ideals aren’t they? Foreground, middle ground and perspective, which is the third dimension and which is also parallel to the discovery of science.... Einstein’s discovery of the cosmos is the infinite dimension, without end. And here we have the foreground, middle ground and background, what do I have to do to go further? I make a hole, infinity passes through it, light passes through it, there is no need to paint...everyone thought I wanted to destroy; but it is not true, I have constructed’ (Fontana in conversation with Carla Lonzi, 1967, quoted in C. Lonzi, Autoritratto, Bari, 1969 p. 176).

It was through the cut that Fontana succeeded, with a single, simple and irrevocable gesture, to achieve a perfect expression of these concepts in his art. When, in 1958, he first sliced through the canvas, he discovered that he could not only transform the previously inviolable pictorial surface into a three-dimensional object that interacted and coexisted with the space surrounding it, but, by revealing the black, empty and seemingly endless space beyond the surface of the canvas, he could offer the viewer a glimpse of the infinite—a view of the fourth dimension. “When I hit the canvas I sensed that I had made an important gesture”, he explained. “It was, in fact, not an incidental hole, it was a conscious hole: by making a hole in the picture I found a new dimension in the void. By making holes in the picture I invented the fourth dimension” (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, p. 21). Just as scientists and astronauts were altering the limits of human consciousness with their scientific discoveries and technological inventions, so Fontana pioneered a new form of art that offered a new way of seeing and thinking about the world.

While the tagli are distinctly of their time, conceived as the embodiment of the epoch in which they were created, with the slash Fontana believed he had invented a gesture that would transcend the boundaries of earthly time. The cut was an eternal gesture that, unlike the material itself, which would inevitably decay over years, existed without end. “We plan to separate art from matter”, he had declared in the Primo Manifesto Spaziale of 1947, “to separate the sense of the eternal from the concern with the immortal. And it doesn’t matter to us if a gesture, once accomplished, lives for a moment or a millennium, for we are convinced that, having accomplished it, it is eternal” (Primo Manifesto Spaziale, 1947, op. cit., p. 118). It was with works such as Concetto Spaziale, Attese, that Fontana achieved an absolute clarity, the highly concentrated act of slicing the canvas serving as the climax of his artistic explorations. As he stated, “With the taglio I have invented a formula that I think I cannot perfect… I succeeded in giving those looking at my work a sense of spatial calm, of cosmic rigour, of serenity with regard to the Infinite. Further than this I could not go” (Fontana, quoted in Gottschaller, op. cit., p. 58).

The inherently emancipatory nature of the slashes is also reflected in the sense of anticipatory optimism evoked by the titles of the tagli themselves. Every Attesa or ‘expectation’, a word often affixed to the title of Fontana’s slash paintings, evokes not just the immeasurable space beyond the surface of the earth, but also the vastness of the human mind. Opening up the boundaries previously instilled by the confines of the canvas, Fontana was likewise seeking to expand the confines of human consciousness, leading the viewer into a new realm of heightened spiritual awareness. Embodying the mystery of an unknown future, these works are endowed with a visionary dimension. As Fontana stated, “In future there will no longer be art the way we understand it… No, art, the way we think about it today will cease…there’ll be something else. I make these cuts and these holes, these Attese and these Concetti… Compared to the Spatial era I am merely a man making signs in the sand. I made these holes. But what are they? They are the mystery of the Unknown in art, they are the Expectation of something that must follow” (Fontana, quoted in Barbero, op. cit., p. 47). Fontana often inscribed personal, philosophical or anecdotal details on the versos of his Attesa, endowing some of these works with specific autobiographical meanings or memories. In the case of the present work, Fontana has added the line, “Today I am having breakfast with the painter Clee”, a reference to the artist Clelia Cortemiglia, an artist who was a close friend and also student of Fontana.

The artwork described above is subject to changes in availability and price without prior notice.

Concetto Spaziale, Attese offers an inexorable commentary on the post-war society in which it was created. Unlike his contemporary Alberto Burri, Fontana chose to turn away from the destruction, both physical and psychological, that the Second World War had wrought upon mankind, and instead focus single-mindedly upon the future, embracing all the possibilities and excitement of this great unknown. Living and working in Italy in the years immediately following the war—Fontana had returned to Milan to find his pre-war studio bombed to the ground, while Burri returned having served as a medic in the Italian army before enduring incarceration in Texas—both artists were similarly impelled to find a new artistic language to embody the post-war period in which they found themselves. While they both believed that traditional modes of painting and sculpture had no place in the post-war era, they found radically different modes of expression with which to better express the paradoxical sentiments that beset these strange and unprecedented times.

As Fontana declared, “Man today is too bewildered by the vastness of his world, he is too overwhelmed by the triumph of Science, he is too dismayed by the new inventions which follow one after the other, to be able to find himself in figurative painting. What is needed is an absolutely new language, a ‘Gesture’ purifed of all ties with the past, which gives expression to this state of despair, of existential anguish’ (Fontana, quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, Venice, and Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2006–7, p. 23).

Fascinated by science and technology, Fontana looked resolutely skywards, watching with ever increasing awe as the earth’s atmosphere was breached, first with satellites, and then as man himself conquered space. Fontana was determined, as the Futurists had been before him, to ensure that his art reflect these pioneering new advances, quickly recognising that painting and sculpture were too inherently limited to convey the extraordinary concepts of space and time so recently discovered. In the face of explosive technological and scientific innovation and change, what use, he asked, did illusionistic painted representations on canvas have? “Think about when there are big space stations”, he asked. “Do you think that the men of the future will build columns with capitals there? Or that they will call painters to paint?... No, art, as it is thought of today, will end” (Fontana, quoted in A. White, “Art Beyond the Globe: Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Identity,” emaj, 3, 2008, p. 2).

Contemporary art, Fontana believed, needed to come out of its frame and off its pedestal to incorporate and therefore exist in real time, space and movement. It was upon his return to Milan in 1947 following a seven-year sojourn in Buenos Aires that these ideas took shape. While in Argentina, he had already published a manifesto, the Manifesto Blanco, in which, borrowing the rhetoric of his Futurist forebears, Fontana denounced traditional forms of painting and sculpture, instead calling for an art that embodied the spirit of the intrepid, rapidly changing times. “We need a change in essence and in form”, the manifesto declared. “We need to go beyond painting, sculpture, poetry, and music. We need a greater art in harmony with the requirements of the new spirit” (Manifesto Blanco, 1946, quoted in E. Crispolti and R. Siligato, eds., Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, 1998, p. 115). A year later, Fontana presented a second tract entitled Primo Manifesto Spaziale, which presented the central tenets of Fontana’s newly-founded Spatialism, the movement to which he would remain devoted for the rest of his career. “We refuse to believe that science and art are two distinct facts, that the gestures accomplished by one of the two activities cannot also belong to the other”, Fontana declared in this text, surmising the central aspects of the movement. “Artists anticipate scientific gestures, scientific gestures always provoke artistic gestures” (Primo Manifesto Spaziale, 1947, quoted in ibid., p. 118).

Along with the space race, Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity had hit Fontana with the force of a revelation. Discovering the scientist’s revolutionary concepts, Fontana sought in his art to look beyond the bounds of reality and representation: just as Einstein expounded the existence of the fourth dimension, so Fontana sought to capture this concept in artistic form. “Spatial is what is beyond the perspective...the discovery of the cosmos...Which are all ideals aren’t they? Foreground, middle ground and perspective, which is the third dimension and which is also parallel to the discovery of science.... Einstein’s discovery of the cosmos is the infinite dimension, without end. And here we have the foreground, middle ground and background, what do I have to do to go further? I make a hole, infinity passes through it, light passes through it, there is no need to paint...everyone thought I wanted to destroy; but it is not true, I have constructed’ (Fontana in conversation with Carla Lonzi, 1967, quoted in C. Lonzi, Autoritratto, Bari, 1969 p. 176).

It was through the cut that Fontana succeeded, with a single, simple and irrevocable gesture, to achieve a perfect expression of these concepts in his art. When, in 1958, he first sliced through the canvas, he discovered that he could not only transform the previously inviolable pictorial surface into a three-dimensional object that interacted and coexisted with the space surrounding it, but, by revealing the black, empty and seemingly endless space beyond the surface of the canvas, he could offer the viewer a glimpse of the infinite—a view of the fourth dimension. “When I hit the canvas I sensed that I had made an important gesture”, he explained. “It was, in fact, not an incidental hole, it was a conscious hole: by making a hole in the picture I found a new dimension in the void. By making holes in the picture I invented the fourth dimension” (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, p. 21). Just as scientists and astronauts were altering the limits of human consciousness with their scientific discoveries and technological inventions, so Fontana pioneered a new form of art that offered a new way of seeing and thinking about the world.

While the tagli are distinctly of their time, conceived as the embodiment of the epoch in which they were created, with the slash Fontana believed he had invented a gesture that would transcend the boundaries of earthly time. The cut was an eternal gesture that, unlike the material itself, which would inevitably decay over years, existed without end. “We plan to separate art from matter”, he had declared in the Primo Manifesto Spaziale of 1947, “to separate the sense of the eternal from the concern with the immortal. And it doesn’t matter to us if a gesture, once accomplished, lives for a moment or a millennium, for we are convinced that, having accomplished it, it is eternal” (Primo Manifesto Spaziale, 1947, op. cit., p. 118). It was with works such as Concetto Spaziale, Attese, that Fontana achieved an absolute clarity, the highly concentrated act of slicing the canvas serving as the climax of his artistic explorations. As he stated, “With the taglio I have invented a formula that I think I cannot perfect… I succeeded in giving those looking at my work a sense of spatial calm, of cosmic rigour, of serenity with regard to the Infinite. Further than this I could not go” (Fontana, quoted in Gottschaller, op. cit., p. 58).

The inherently emancipatory nature of the slashes is also reflected in the sense of anticipatory optimism evoked by the titles of the tagli themselves. Every Attesa or ‘expectation’, a word often affixed to the title of Fontana’s slash paintings, evokes not just the immeasurable space beyond the surface of the earth, but also the vastness of the human mind. Opening up the boundaries previously instilled by the confines of the canvas, Fontana was likewise seeking to expand the confines of human consciousness, leading the viewer into a new realm of heightened spiritual awareness. Embodying the mystery of an unknown future, these works are endowed with a visionary dimension. As Fontana stated, “In future there will no longer be art the way we understand it… No, art, the way we think about it today will cease…there’ll be something else. I make these cuts and these holes, these Attese and these Concetti… Compared to the Spatial era I am merely a man making signs in the sand. I made these holes. But what are they? They are the mystery of the Unknown in art, they are the Expectation of something that must follow” (Fontana, quoted in Barbero, op. cit., p. 47). Fontana often inscribed personal, philosophical or anecdotal details on the versos of his Attesa, endowing some of these works with specific autobiographical meanings or memories. In the case of the present work, Fontana has added the line, “Today I am having breakfast with the painter Clee”, a reference to the artist Clelia Cortemiglia, an artist who was a close friend and also student of Fontana.

The artwork described above is subject to changes in availability and price without prior notice.