Alighiero Boetti

b. 1940, Turin, Italy

d. 1994, Rome, Italy

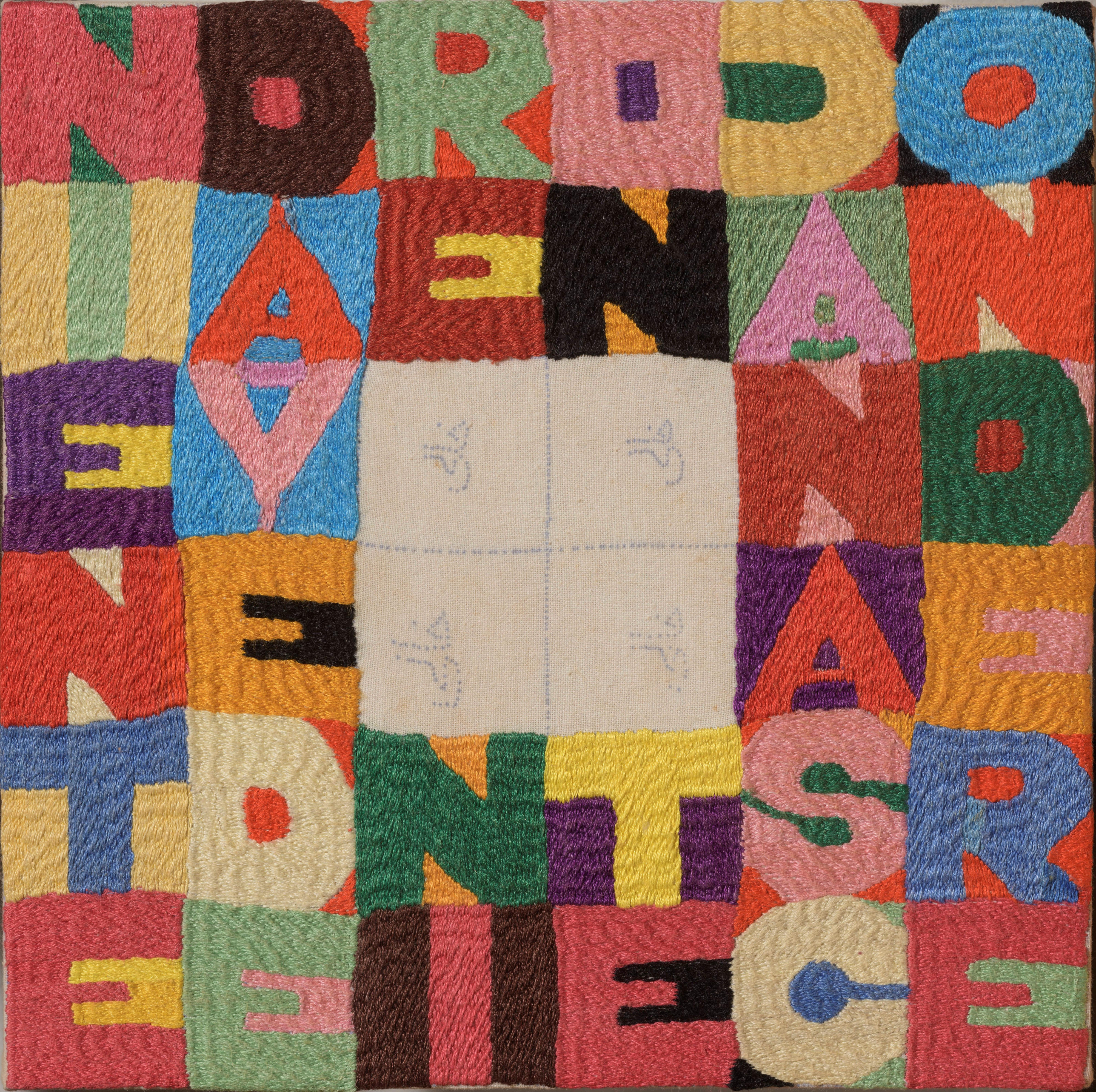

Niente da vedere niente da nascondere (Nothing to see, nothing to hide)

1989

Embroidery

25 x 26.2 cm (9 7/8 x 10 1/4 in.)

Provenance

Description

Alighiero Boetti was one of the most influential figures of Italian art in the second half of the twentieth century. Born in Turin in 1940, he was a founding member of the Arte Povera movement. In the early 1970s, he disassociated himself from the group and moved to Rome, where he began to sign his work as ‘Alighiero e Boetti’, as though he were two artists in one. Developing a profound engagement with Afghanistan, its culture and people, Boetti undertook a series of projects from 1971 to 1994 where he worked together with female Afghan embroiderers to create his iconic and compelling tapestries. Boetti first worked in Kabul, and then, following the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in 1979, in the refugee camps of Pakistan. A cross-cultural dialogue between the West and East underpins much of Boetti’s work and for this reason he often integrated letters, words and characters of different cultural strands into his embroidered writing pictures.

Niente da vedere niente da nascondere (Nothing to see, nothing to hide) is an example of Boetti’s piccoli ricami; small, embroidered squares with colourful grids of letters spelling various words and phrases. Other such series include embroideries constructed from the words Attirare l’Attenzione, Fuso ma non confuso and other light-hearted sayings. Whenever he came across an expression, whether a line from poetry, a proverb or an aphorism, Boetti claimed to know instinctively whether the number of letters allowed it to be set in a square. His interest in this configuration was rooted in the mathematical laws of the magic square deriving from the Arabic tradition, in which the sum of the rows, columns, and diagonals remains constant.

In the present work, a grid of six-by-six letters interrupted with a two-by-two grid at the centre, reconfigures this straightforward phrase into an alternative system of codification and meaning. In this arazzo as in others, Boetti arranges the letters in unconventional orders to Western eyes, and the reader is forced to read top to bottom to decipher the meaning. In this way, the letters are removed from their written context and impose a chaos which challenges the viewer to adopt new ways of reading; through colour and texture, each letter is aestheticised and transformed into an autonomous form. It is notable that in this particular arazzo, there is the letter 'O' in the fourth column from the left where there should be the letter 'E' - this may have been intentional, to further mask the sense of the words, or may have been an error on the part of Boetti (who designed the pattern for the embroidery), or on the part of the embroiderers, who were unfamiliar with the Roman alphabet and Italian language that they were following. Either way, the substitution makes this arazzo unique among other Niente da vedere works.

Although the phrase itself – nothing to see, nothing to hide – suggests transparency of meaning, this significance is only evident to the viewer after deciphering the order in which the words must be read. Indeed, the inclusion of the Farsi word meaning ‘empty’ in the centre squares further highlights the disjuncture between viewing and understanding, knowing that this textual element of the embroidery would be indecipherable to most of his Western audience. This duality and conflict between the form and the content of an artwork is characteristically Boettian, showing his playful approach to language, and forcing the viewer to reconsider their preconceptions and look afresh at familiar tropes, while also integrating different cultural knowledge systems.

Since the arazzi are hand-embroidered by various anonymous women, each one is distinctive; not only in terms of the colours employed, but also in their slightly differing shapes and sizes. As Boetti himself once notes, ‘I’ve produced a hundred examples of each of these pieces. But each one is different from the others because of its colours and differences in the style of embroiderer. They are neither originals nor multiples: they belong to a new category and to a market that is quite different to that for my other works. Someone once told me I had created the first popular conceptual art’. (Alighiero Boetti in ‘Afghanistan’, statements collected by N. Bourriaud, Documents sur l’art contemporain, 1, October 1992, reprinted in Alighiero Boetti: 1965-1994, exh. cat., Turin, 1996, p. 215).